If the idea of your loved ones leaving this earth never to return again seems unfair, then you should consider the Japanese view of the afterlife. While nothing can change death itself, it is comforting to know that in Japan there is a special time of the year when the souls of the dead come back to visit the living. This is called Bon (or Obon using the honorific “o”) a holiday period from August 12-16 (exact dates may vary depending upon location), a time when the entire country takes a break to celebrate the “festival of the dead.” It’s a lively few days when the living and the dead can once again unite to eat together, drink together and share good times.

The Bon tradition gives the country some of the unique dances that Japan is so famous for. Tokushima’s Bon dance, called Awa Odori, for example, draws over one million tourists every year. Traditional Bon entertainment is so lively, colorful and intriguing that a Bon dance is a must-see on every traveler’s itinerary.

Today we’ll introduce you to a five things you should know about Obon. Needless to say, it’s a very exciting time to be in Japan as a tourist!

While the Bon festival starts around Aug. 12, towns and cities hosting Bon dances have likely been planning for months in advance. Dance practices, the blocking off and closing down of city streets, and the taking of bookings for hotels and restaurants keep everyone busy up to the last minute. In Tokushima, accommodations are so full of tourists who wish to experience the Awa Odori, that those who can’t find a room end up sleeping on the floor of the train station. And believe me, it’s worth it!

While some bon traditions may vary according to the region of Japan, here are some things you can expect to see at Obon no matter where you are in the country:

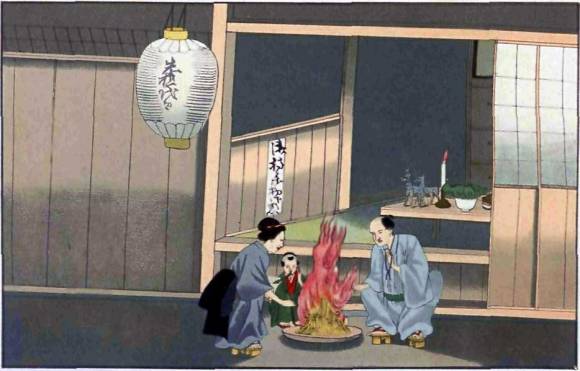

1. Welcome fire 迎え火/mukaebi

On the first day of Obon, people set out lanterns, the light of which is meant to guide the spirits back to their homes. These electrified paper lanterns (or sometimes very small fires lit outside the home) are placed inside the house or, if it’s the first Bon holiday after a family member has passed away, it will be more conspicuously placed outside the house to help the spirit find its way back for the first time. Some people will have fires at the family grave, burning natural fuels such as wood or husks to feed the fire.

On Shiraishi Island, where I live in the Seto Inland Sea, the temple holds a fire ceremony to welcome back all of the souls of the people who have lived on the island.

2. Offerings of food, drinks, sweets お膳/ozen

▼ A mold for sweets in the shape of the lotus.

Inside the homes, offerings of fruit, rice, green tea, sake and special handmade sweets, especially those in the shape of lotus leaves, are offered at the family’s Buddhist altar. Food, when shared with the dead, is called ozen and can be small and simple offerings or larger meals. This reunion with the dead is an attempt to treat the spirits as if they are still alive.

3. Grave visits and cleaning 御墓参り/ohakamairi

Obon is also a time when the family visits the graves of the ancestors. They perform the ritual cleaning of the grave stones, something like outdoor housekeeping. Using a brush they wash away any dirt or stains, then rinse off the stone using a special pail of water and ladle for this purpose. Thus you’ll always find a water tap at graveyards in Japan.

4. Bon Dances 盆踊り/bonodori

Bon dances started hundreds of years ago as religious and spiritual acts. The dances generally take place around a yagura, a central raised platform from which one person sings out a tune and others play traditional instruments such as a taiko drum. The dancers perform the same steps simultaneously, while moving in a large circle around the yagura. Others styles do exist such as the Awa Odori, performed with small entourages of dancers who move around the city streets in their own smaller circles. These dances were traditionally performed from evening until the early morning hours. Perhaps that’s why some believe the dances were great for match-making.

▼ A participant in traditional costume performing in Tokushima’s Awa Odori.

Hundreds of dancers practice for weeks leading up to the Awa Odori festival. The odori is performed to choreographed traditional music that includes lutes, taiko drums, shamisen and bells.

There still exist Bon dances performed for ritualistic purposes rather than entertainment. The Shiraishi Odori has been performed for over 700 years and was used as a vehicle to pray for the souls of the fallen warriors in the sea battles of the Gempei Wars (1180-1185). It is still performed every day of the Bon period for this purpose and is a designated National Intangible Cultural Property in Japan. Because of the island’s small population of just 548 people the production retains a sober, yet intimate feel, and is performed on the beach at sunset with one large group of performers who move slowly and deliberately around the yagura. The ensemble encompasses seven different dance routines, each with a different costume, and is danced by all islanders, most of whom are named Amano, from elementary school children to the elderly.

▼Men dancing the Shiraishi Odori, performed on the beach at sunset.

(Tadashi Amano)

The Shiraishi Bon Dance is taught at the local school, staring in kindergarten. As the children grow up dancing every year for Obon, and throughout the weeks of practices, they cultivate a relationship with the dance that includes learning how to use the implements (fans, straw hats, etc) and how to play the taiko drum to appease the spirits of the fallen Heike warriors.

This video shows an exhibition dance put on by the islanders just before Obon. While the video does not use the original music, it does show the intricacies of the dance, the costumes and the spirit of the island people.

5. Seeing off the spirits: 送り火/灯籠流し/okuribi/toronagashi

At the end of the Bon period it’s time for the ancestors to return to where they came from. The family sees them off with another fire and, if the location is near water, lanterns may be set out on the river or sea in a ceremony called toronagashi. Shiraishi Island has both a fire ceremony sponsored by the temple, as well as a toronagashi, where candles are lit inside paper lanterns and set out floating on the sea, each candle representing a soul of the ancestors.

There are other forms of sending off ceremonies such as Kyoto’s famous Daimonji Gozan Okuribi, or “Daimonji” for short, which are five fires lit on the slopes of mountains around Kyoto Basin. These formations, the most famous being the kanji character 大/dai (big), are said to be for sending off the spirits of the ancestors on August 16, the end of Obon.

▼ The kanji character “dai” on the side of the mountain at the end of Obon.

▼ Toronagashi

It’s hard not to agree that Obon is a beautiful tradition. It brings family together from all over the nation and further unites them with siblings, cousins, parents, grandparents, great grandparents and all those before them. But the biggest beneficiaries are probably the ancestors themselves, who get to meet and spend time with family old and new, even if just spiritually.

The Bon holiday starts next week and I bet our Rocketeers have some great recommendations for you based on their own experiences! Which Bon dances would you recommend visitors try to see?

Feature image: Flickr (Rosino)

Japan petitions to add 40 traditional folk dances to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list

Japan petitions to add 40 traditional folk dances to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list First-ever Bon-Odori dance festival to be held at Shibuya scramble crossing for Obon

First-ever Bon-Odori dance festival to be held at Shibuya scramble crossing for Obon Tokyo Bon Japanglish song is a crazy way to learn Japanese 【Video】

Tokyo Bon Japanglish song is a crazy way to learn Japanese 【Video】 Shiraishi Island needs YOUR character ideas!

Shiraishi Island needs YOUR character ideas! Funky food-themed swaddling cloths let you wrap your baby up like sushi, egg rolls, or tortillas

Funky food-themed swaddling cloths let you wrap your baby up like sushi, egg rolls, or tortillas Red light district sushi restaurant in Tokyo shows us just how wrong we were about it

Red light district sushi restaurant in Tokyo shows us just how wrong we were about it Akihabara pop-up shop sells goods made by Japanese prison inmates

Akihabara pop-up shop sells goods made by Japanese prison inmates McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods Beautiful Red and Blue Star luxury trains set to be Japan’s new Hokkaido travel stars

Beautiful Red and Blue Star luxury trains set to be Japan’s new Hokkaido travel stars Anime girl English teacher Ellen-sensei becomes VTuber/VVTUber and NFT

Anime girl English teacher Ellen-sensei becomes VTuber/VVTUber and NFT Sandwiches fit for a sumo served up in Osaka【Taste Test】

Sandwiches fit for a sumo served up in Osaka【Taste Test】 Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes

Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes Historical figures get manga makeovers from artists of Spy x Family, My Hero Academia and more

Historical figures get manga makeovers from artists of Spy x Family, My Hero Academia and more Limited-edition Carbonara Udon will anger noodle purists and pasta lovers 【Taste test】

Limited-edition Carbonara Udon will anger noodle purists and pasta lovers 【Taste test】 Tokyo Tsukiji fish market site to be redeveloped with 50,000-seat stadium, hotel, shopping center

Tokyo Tsukiji fish market site to be redeveloped with 50,000-seat stadium, hotel, shopping center All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge

All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month

More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month French Fries Bread in Tokyo’s Shibuya becomes a hit on social media

French Fries Bread in Tokyo’s Shibuya becomes a hit on social media Studio Ghibli releases new action figures featuring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind characters

Studio Ghibli releases new action figures featuring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind characters New private rooms on Tokaido Shinkansen change the way we travel from Tokyo to Kyoto

New private rooms on Tokaido Shinkansen change the way we travel from Tokyo to Kyoto Starbucks reopens at Shibuya Scramble Crossing with new look and design concept

Starbucks reopens at Shibuya Scramble Crossing with new look and design concept Studio Ghibli glasses cases let anime characters keep an eye on your spectacles

Studio Ghibli glasses cases let anime characters keep an eye on your spectacles Beautiful Ghibli sealing wax kits let you create accessories and elegant letter decorations【Pics】

Beautiful Ghibli sealing wax kits let you create accessories and elegant letter decorations【Pics】 Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan

Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers

New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things

Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro

Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty

New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions

New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo

Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions

One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint

We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan Organizers angered as ceremonial giant kanji “fire” in Kyoto lit early and unofficially

Organizers angered as ceremonial giant kanji “fire” in Kyoto lit early and unofficially Hello Kitty dances the traditional Bon Odori dance on new Japanese summer kimono

Hello Kitty dances the traditional Bon Odori dance on new Japanese summer kimono Japanese taxi company offers service to visit family graves for those who can’t travel themselves

Japanese taxi company offers service to visit family graves for those who can’t travel themselves The 100 Soundscapes of Japan: A list of Japan’s greatest natural, cultural, and industrial sounds

The 100 Soundscapes of Japan: A list of Japan’s greatest natural, cultural, and industrial sounds What’s white and sweet and smells like your first love? This tart made from white strawberries!

What’s white and sweet and smells like your first love? This tart made from white strawberries! Cat photographer captures fascinating shots of our feline friends dancing and practicing kung fu

Cat photographer captures fascinating shots of our feline friends dancing and practicing kung fu Costume-less Chinese lion dance videos show real humans, real behind-the-scenes magic【Video】

Costume-less Chinese lion dance videos show real humans, real behind-the-scenes magic【Video】 The Great Obon Disaster: A fable of cicadas, dancing, and cats

The Great Obon Disaster: A fable of cicadas, dancing, and cats Boot camps and desertion in the mountains among the ways Japanese companies train new recruits

Boot camps and desertion in the mountains among the ways Japanese companies train new recruits Japan’s secret garbage problem–and what you can do to help

Japan’s secret garbage problem–and what you can do to help There’s more to do than just look at the flowers at Tokyo’s biggest riverside sakura celebration

There’s more to do than just look at the flowers at Tokyo’s biggest riverside sakura celebration Good news for lazy folk: Japan’s government to consider creating a new public holiday

Good news for lazy folk: Japan’s government to consider creating a new public holiday Travis Japan members compete with the best dancers in Japan at Red Bull’s national dance finals

Travis Japan members compete with the best dancers in Japan at Red Bull’s national dance finals Quite possibly the otaku-ist dance that any otaku has ever danced【Video】

Quite possibly the otaku-ist dance that any otaku has ever danced【Video】 They’re back! Pikachus overrun Yokohama for second straight year and dance up a storm! 【Videos】

They’re back! Pikachus overrun Yokohama for second straight year and dance up a storm! 【Videos】 These wacky traditional dancers know how to put the fun in fundoshi! 【Video】

These wacky traditional dancers know how to put the fun in fundoshi! 【Video】

Leave a Reply