Whether resolving a dispute, deciding who pays the check for lunch, or simply passing the time, Japan’s “Jan-ken” culture is simple, surprisingly elegant, and a lot of fun.

In Western cultures, you might go back and forth with someone when deciding who picks up the check at a restaurant, each party becoming increasingly flustered with the whole, “I’ve got this,” “No, no. I’ve got this!” song and dance until someone finally gives in. In Japan, this situation would be quickly and efficiently resolved with a good old-fashioned game of rock-paper-scissors.

Rock-paper-scissors, or “Jan-ken” in Japanese, is a cultural keystone in Japan, with all kinds of disputes, disagreements, and predicaments being resolved through the game’s simplistic mechanics.

Kids in Japan are taught about jan-ken at a young age, and it’s a quick and easy way for parents to let kids resolve common sibling altercations through the impartial hand of Lady Luck. Sure, there are pro rock-paper-scissors leagues that meticulously calculate odds and discuss strategy, but for two adolescents in Japan, jan-ken is about the closest thing to a fair and largely luck-based resolution you’re liable to find. Kids learn that the result of a good jan-ken game is indisputable, so there are few complaints when a child loses that last piece of cake or whatnot to his younger sister.

▼ A Japanese YouTuber challenges a random store clerk to a game of jan-ken

The idea that jan-ken is a simple and fair solution for many of life’s social conundrums carries on into adulthood, where rock-paper-scissors matches are held to decide everything from who should pay the check at dinner, to who gets that shiny new PS4 at the office end-of-year party. In fact, it’s not unheard of for extremely costly transactions to be decided with rock paper scissors, such as this auction house that settled a tied bid by having the bidders engage in a game of jan-ken.

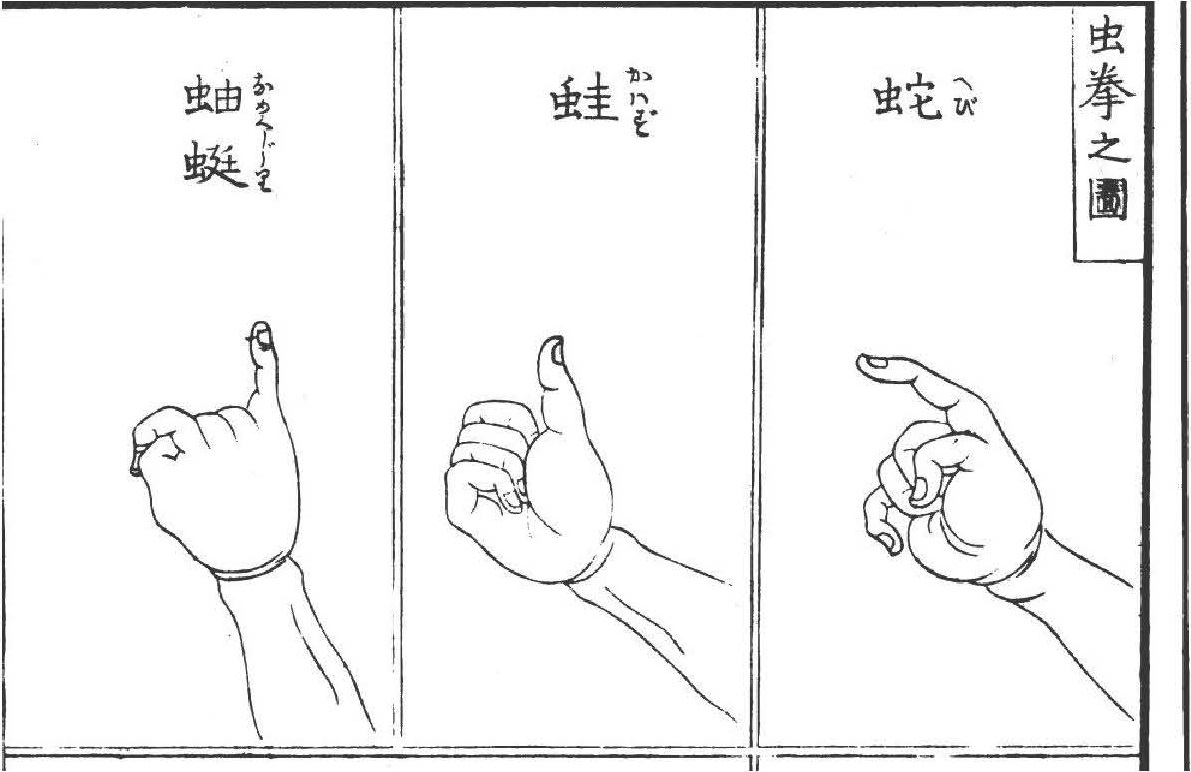

Rock-paper-scissors apparently originated in China (or, at least, that’s where the first historical mention of the game came from), and it’s used occasionally in western cultures to make mostly inconsequential decisions, but it’s arguably the Japanese that elevated jan-ken to an entrenched form of social interaction, starting with a variation called “Kitsune-ken” that used a similar rule set. The featured image depicts a trio of women playing the fox (“kitsune” in Japanese) version of the game.

▼ A diagram of how to play “Mushi-ken,” a precursor to Japan’s jan-ken

Jan-ken is so ingrained into Japanese culture that it pops up everywhere. Restaurants and bars will often hold promotions that challenge guests to play a match with waiters and waitresses for a free drink or a discount. It’s also a common drinking game among friends and it’s so ubiquitous that there are countless permutations in the rules for how to resolve a tie or win the game. At least one university has even sunk significant manpower and resources into creating a robotic arm that wins jan-ken games 100% of the time.

▼ Fortunately, they still don’t let it make any decisions.

While western cultures may decide things with a coin toss, don’t be surprised if you’re challenged to a game of jan-ken when visiting Japan – sometimes even when the stakes are fairly high. Just remember the phrase for initiating a game (“saisho wa gu, jan-ken-pon!“) and enjoy the simple beauty of knowing that, statistically, at least, you’ll win just as often as you lose.

Feature Image: Wikipedia/Victoria and Albert Museum

Insert Image: Wikipedia/Linhart, Sepp

Japanese netizens dismayed at abysmal win rate of Pepsi Japan’s rock-paper-scissors promotion

Japanese netizens dismayed at abysmal win rate of Pepsi Japan’s rock-paper-scissors promotion Tokyo University students rank the top 12 video games for cultivating smart kids

Tokyo University students rank the top 12 video games for cultivating smart kids “Are you married yet?” – Chinese ad attempts to guilt-trip young women into trying the knot

“Are you married yet?” – Chinese ad attempts to guilt-trip young women into trying the knot “Bully insurance” now on the rise, with many more practical uses than just insuring bullying

“Bully insurance” now on the rise, with many more practical uses than just insuring bullying Japanese soccer fans remember their manners in Brazil, clean up before going home

Japanese soccer fans remember their manners in Brazil, clean up before going home McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods Super Nintendo World expansion gets delayed for several months at Universal Studios Japan

Super Nintendo World expansion gets delayed for several months at Universal Studios Japan Studio Ghibli glasses cases let anime characters keep an eye on your spectacles

Studio Ghibli glasses cases let anime characters keep an eye on your spectacles All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge

All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge Beautiful Sailor Moon manhole cover coasters being given out for free by Tokyo tourist center

Beautiful Sailor Moon manhole cover coasters being given out for free by Tokyo tourist center Kyoto’s 100 Demons yokai monster parade returns!

Kyoto’s 100 Demons yokai monster parade returns! Mister Donut ready to make hojicha dreams come true in latest collab with Kyoto tea merchant

Mister Donut ready to make hojicha dreams come true in latest collab with Kyoto tea merchant More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month

More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month My Neighbour Totoro kimono coat sells out as soon as it’s released by Studio Ghibli in Japan

My Neighbour Totoro kimono coat sells out as soon as it’s released by Studio Ghibli in Japan Randomly running into a great sushi lunch like this is one of the best things about eating in Tokyo

Randomly running into a great sushi lunch like this is one of the best things about eating in Tokyo Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo

Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo Starbucks reopens at Shibuya Scramble Crossing with new look and design concept

Starbucks reopens at Shibuya Scramble Crossing with new look and design concept Beautiful new Final Fantasy T-shirt collection on the way from Uniqlo【Photos】

Beautiful new Final Fantasy T-shirt collection on the way from Uniqlo【Photos】 Is the new Shinkansen Train Desk ticket worth it?

Is the new Shinkansen Train Desk ticket worth it? Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】

Foreign English teachers in Japan pick their favorite Japanese-language phrases【Survey】 Japanese convenience store packs a whole bento into an onigiri rice ball

Japanese convenience store packs a whole bento into an onigiri rice ball We try out “Chan Ramen”, an underground type of ramen popular in the ramen community

We try out “Chan Ramen”, an underground type of ramen popular in the ramen community Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan

Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan Japan’s bone-breaking and record-breaking roller coaster is permanently shutting down

Japan’s bone-breaking and record-breaking roller coaster is permanently shutting down New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers

New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things

Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro

Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro Foreign passenger shoves conductor on one of the last full runs for Japan’s Thunderbird train

Foreign passenger shoves conductor on one of the last full runs for Japan’s Thunderbird train Domino’s Japan now sells…pizza ears?

Domino’s Japan now sells…pizza ears? New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty

New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty Kyoto creates new for-tourist buses to address overtourism with higher prices, faster rides

Kyoto creates new for-tourist buses to address overtourism with higher prices, faster rides Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions

One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint

We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan Japanese nerds pick the feudal warlord they’d most like to be their boss

Japanese nerds pick the feudal warlord they’d most like to be their boss Amahiko Sato becomes first pro shogi player in history to lose game for not wearing face mask

Amahiko Sato becomes first pro shogi player in history to lose game for not wearing face mask Japanese city makes list of world’s top 10 most livable cities, but not one most people expected

Japanese city makes list of world’s top 10 most livable cities, but not one most people expected The five least stressful jobs, as ranked by Japanese working people

The five least stressful jobs, as ranked by Japanese working people Japanese director alleges that beloved children’s anime Doraemon is “banned” in France

Japanese director alleges that beloved children’s anime Doraemon is “banned” in France Does the experience of living in Japan make you a better person? The good, bad and ugly

Does the experience of living in Japan make you a better person? The good, bad and ugly Suika Game can now help you stay in shape with new exercise version of the smash-hit game【Video】

Suika Game can now help you stay in shape with new exercise version of the smash-hit game【Video】 Yakuza 6 to feature baddest Yakuza film dude of all time: Japanese actor Beat Takeshi 【Video】

Yakuza 6 to feature baddest Yakuza film dude of all time: Japanese actor Beat Takeshi 【Video】 Spider-Man director to reboot horror flick The Grudge

Spider-Man director to reboot horror flick The Grudge 50-year-old otaku murders father who criticized his anime and game hobbies

50-year-old otaku murders father who criticized his anime and game hobbies 5 powerful reasons to be a woman in Japan 【Women in Japan Series】

5 powerful reasons to be a woman in Japan 【Women in Japan Series】 Mr. Sato attempts to conquer mountains of shaved ice at all-you-can-eat event

Mr. Sato attempts to conquer mountains of shaved ice at all-you-can-eat event Video shows that Street Fighter V’s story mode is so easy even a baby can beat it 【Video】

Video shows that Street Fighter V’s story mode is so easy even a baby can beat it 【Video】 LED plant factories offer efficient 3D alternative to traditional gardening

LED plant factories offer efficient 3D alternative to traditional gardening Manhole Holy War breaks out in Tokyo, winners get money and help repair city infrastructure

Manhole Holy War breaks out in Tokyo, winners get money and help repair city infrastructure Take a look around Tokyo Game Show 2016 with us!【Photos】

Take a look around Tokyo Game Show 2016 with us!【Photos】

Leave a Reply