Japanese Twitter alights over one of the great mysteries of the cat world.

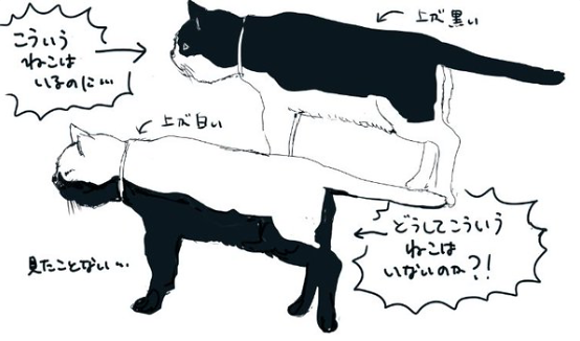

For all the time we’ve spent watching cat-related videos on the internet and idly scrolling through cute pictures of kittens on our phones, there was one thought that never crossed our minds: why don’t black-and white cats have pale backs and dark bellies? This is exactly the question that one Twitter user thought to ask last week, and the answers that are coming to light are almost as puzzling as the question posed.

▼ Ami Sugimoto was so intrigued by the elusive colour combination that she drew an anime-style sketch to illustrate her point. The black-and-white cat on the right is often seen, but why not a cat-like the one on the left?

いつもねこの事で疑問に思っている pic.twitter.com/xaTNTFGwPm

— 杉本亜未 (@SugimotoAmiInfo) May 31, 2016

With thousands of retweets, fellow Twitter users have been scratching their heads over the concept. One person, however, presented an interesting theory as to the reason why this occurs. According to @Valquasard, we have to go right to the very early stages of embryonic development to understand the entire process. While animals all carry a specific combination of genes which influence the colouring and patterns they will be born with, cells play a large part in producing those colours and patterns.

基本は色素の無い白色で、発生過程で色素を作る細胞が脊椎付近に発生→色素と対抗因子のT.ウェーブにより斑紋や縞模様に、初期に色素因子が多すぎると単一色に… で腹まで広がらないところで止まれば、背黒腹白模様に。

— バルカサード (@Valquasard) May 31, 2016

With white being the natural, unpigmented shade, as the embryo develops, the cells responsible for pigmentation move downwards from the vicinity of the spinal area. As these pigmentation cells migrate they encounter inhibitors, causing T-wave patterns that may form speckles or stripes. For solid colours, the cells responsible for pigmentation will migrate from the back and all the way to the front of the animal. In the case of two-tone piebald cats however, these cells stop before the journey is complete, creating the black-back-white-belly combination we see today.

▼ Sometimes the pigmentation cells move randomly, which explains the reason for the adorable love-heart shape on the chest of current Instagram star Zoe the cat

Musing on the wonders of the world and nature’s ability to form seemingly random patterns and markings, @Valquasard then dived deeper, bringing up the mystery of Fibonacci number patterns which occur frequently in nature; a system of numbering that can be reflected in the growth and development of a wide variety of living things like leaf and petal arrangements in plants.

「波紋と螺旋とフィボナッチ-数理の眼鏡でみえてくる生命の形の神秘」で、最近知ったばかりのネタです。お時間有ったらどうぞ(背黒腹白の話はなかったかもしれませんが、ヤッコダイやシマウマの模様の話が面白く書かれています)

— バルカサード (@Valquasard) May 31, 2016

Each number in the sequence, which begins with 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, comes from adding the two numbers before it, and is considered to be one of the principal laws of nature. The number of petals on many flowers, for instance, is a Fibonacci number: lilies have three petals, buttercups have five petals and daisies can have 34, 55 or 89 petals. These numbers are also connected to the creation of patterns in butterfly wings, zebra stripes and nautilus shells, suggesting that the series can be related to the growth of every living thing, including cells that create patterns on piebald cats.

▼ If you count the spirals of the seeds in a sunflower in a consistent manner, you will always find a Fibonacci number.

As for the black-and-white cat mystery, Ami Sugimoto, who initially brought the topic to everyone’s attention, was thrilled to receive a plausible explanation to her query, impressed with the ideas put forward by @Valquasard and thanking him for his input. His suggestions are actually in line with pigment cell development theories presented in a number of research papers like this study, which examines the formation of patterns and colours on mice and zebrafish.

As for the reason why pigmentation cells fail to complete their journey of migration to the stomachs of black and white cats, a paper published earlier this year by researchers at the Univeristies of Bath and Edinburgh suggests a faulty gene reduces cell multiplication rates, meaning there aren’t enough pigment cells to cover the entire skin, leaving the animal with a white belly.

This finding may prove useful in studying why cells fail to move to their correct positions during early stages of development, opening up a range of possibilities for further investigation into embryonic diseases. All thanks to the humble piebald cat.

Sources: Togech, Featherland Cattery, BBC World Service Trust, National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine

Top Image: Twitter/@SugimotoAmiInfo (edited by RocketNews24)

Insert Images: Pixabay (1, 2, 3, 4)

Japanese researchers learn how to grow hair follicles, and probably new hair

Japanese researchers learn how to grow hair follicles, and probably new hair Japan now has a traffic safety video for cats to watch to help keep them safe on the streets

Japan now has a traffic safety video for cats to watch to help keep them safe on the streets Dress like your favourite Sailor Moon warrior with these clever fashion coordinates

Dress like your favourite Sailor Moon warrior with these clever fashion coordinates Gundam model enthusiast turns plain smartphone case into amazing work of art

Gundam model enthusiast turns plain smartphone case into amazing work of art TeamLab Borderless: A visitor’s guide to Tokyo’s new jaw-dropping interactive light museum

TeamLab Borderless: A visitor’s guide to Tokyo’s new jaw-dropping interactive light museum Red light district sushi restaurant in Tokyo shows us just how wrong we were about it

Red light district sushi restaurant in Tokyo shows us just how wrong we were about it Sandwiches fit for a sumo served up in Osaka【Taste Test】

Sandwiches fit for a sumo served up in Osaka【Taste Test】 Tokyo Tsukiji fish market site to be redeveloped with 50,000-seat stadium, hotel, shopping center

Tokyo Tsukiji fish market site to be redeveloped with 50,000-seat stadium, hotel, shopping center McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods French Fries Bread in Tokyo’s Shibuya becomes a hit on social media

French Fries Bread in Tokyo’s Shibuya becomes a hit on social media Pokémon Sleep camping suite and guestrooms coming to Tokyo Hyatt along with giant Snorlax burgers

Pokémon Sleep camping suite and guestrooms coming to Tokyo Hyatt along with giant Snorlax burgers Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes

Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes Akihabara pop-up shop sells goods made by Japanese prison inmates

Akihabara pop-up shop sells goods made by Japanese prison inmates Anime girl English teacher Ellen-sensei becomes VTuber/VVTUber and NFT

Anime girl English teacher Ellen-sensei becomes VTuber/VVTUber and NFT Beautiful Ghibli sealing wax kits let you create accessories and elegant letter decorations【Pics】

Beautiful Ghibli sealing wax kits let you create accessories and elegant letter decorations【Pics】 All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge

All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month

More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month Studio Ghibli releases new action figures featuring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind characters

Studio Ghibli releases new action figures featuring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind characters New private rooms on Tokaido Shinkansen change the way we travel from Tokyo to Kyoto

New private rooms on Tokaido Shinkansen change the way we travel from Tokyo to Kyoto Starbucks reopens at Shibuya Scramble Crossing with new look and design concept

Starbucks reopens at Shibuya Scramble Crossing with new look and design concept Studio Ghibli glasses cases let anime characters keep an eye on your spectacles

Studio Ghibli glasses cases let anime characters keep an eye on your spectacles Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan

Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers

New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things

Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro

Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty

New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions

New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo

Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions

One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint

We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan Wasabi found to promote hair growth 3 times faster than minoxidil

Wasabi found to promote hair growth 3 times faster than minoxidil Internet falls in love with cat’s first-ever encounter with carpet

Internet falls in love with cat’s first-ever encounter with carpet Testing out the legendary hair growing power of kinako【RocketScience】

Testing out the legendary hair growing power of kinako【RocketScience】 This rare autumn vegetable is the perfect addition to your stir-fry or salad【SoraKitchen】

This rare autumn vegetable is the perfect addition to your stir-fry or salad【SoraKitchen】 New bizarre Thai trend has men undergoing laser treatment to bleach their penis

New bizarre Thai trend has men undergoing laser treatment to bleach their penis Japanese squat toilet plastic model kit: Weird, gross, or both?【Photos】

Japanese squat toilet plastic model kit: Weird, gross, or both?【Photos】 Japan’s new custom-order cat-theme toilet paper lets you wipe your butt with cuteness

Japan’s new custom-order cat-theme toilet paper lets you wipe your butt with cuteness Starbucks Korea releases adorable lineup of goods for the Year of the Rooster

Starbucks Korea releases adorable lineup of goods for the Year of the Rooster Mock-up Nike x Dragon Ball shoes look so awesome, we wish they were real

Mock-up Nike x Dragon Ball shoes look so awesome, we wish they were real Store your captured cards and other belongings in these Cardcaptor Sakura handbags

Store your captured cards and other belongings in these Cardcaptor Sakura handbags A star is born: Twitter users have a field day with Assemblyman Nonomura’s teary defense

A star is born: Twitter users have a field day with Assemblyman Nonomura’s teary defense What is this kitty trying to tell us? The online mystery of the cat and the cotton swabs

What is this kitty trying to tell us? The online mystery of the cat and the cotton swabs Cup Noodle makers successfully create lab-grown diced steak with authentic texture

Cup Noodle makers successfully create lab-grown diced steak with authentic texture Tailors to Queen of England design ultra-luxurious Gundam cosplay outfit with jaw-dropping price

Tailors to Queen of England design ultra-luxurious Gundam cosplay outfit with jaw-dropping price Anime featuring anthropomorphized blood cells confirmed, actually looks cooler than it sounds

Anime featuring anthropomorphized blood cells confirmed, actually looks cooler than it sounds

Leave a Reply