Though the kanji can translate as “lonely country,” his complaint lies elsewhere.

For the most part, the Japanese language uses the phonetic script called katakana to render the names of places outside Asia. However, as we’ve looked at before, there are also standardized kanji, the characters originally brought over from China, that are also used to refer to foreign countries, especially in newspaper articles and other media reports.

These “country kanji” aren’t necessarily a perfect match up with the nation’s original, or even corrupted katakana, pronunciations, and are instead usually an approximation of the initial syllable. Still, it is kind of cool for people from England, for example, to know that sometimes they’re referred to as being from Eikoku, meaning “Hero Country” or “Glory Country.”

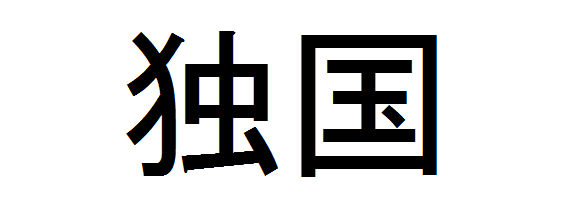

However, Tokyo resident and linguist Christoph Schmitz doesn’t feel so happy when he sees his native Germany rendered as Dokukoku, written in kanji like this:

The first kanji, read doku, was chosen because of its similarity to “Doitsu,” the corrupted Japanese pronunciation of the “Deutsch” portion of “Deutschland,” as Germany is called in the German language. Doku ordinarily means “alone,” and the kanji shows up in such dreary Japanese vocabulary as kodoku (“loneliness”) and dokudan (“arbitrary judgement”), but it’s part of more positive members of the lexicon like dokuritsu (“independence”) and dokusou (“originality”).

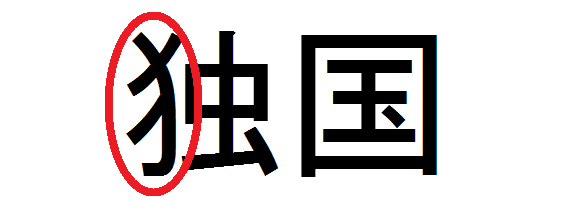

However, Schmitz takes issue not with the meaning of doku, but with how the character is written. The 47-year-old, who recently finished a 12-year project translating and self-publishing an English version of respected Japanese kanji scholar Shizuka Shirakawa’s Lexical Interpretation of General-Use Kanji, is specifically bothered by the left half of the character.

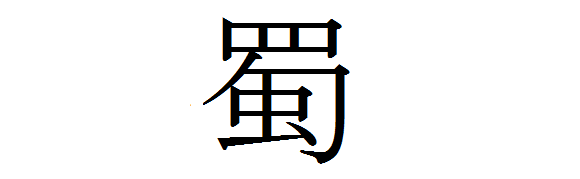

Like many kanji, doku is a compound of other, older kanji, which have had their shapes altered and/or compacted for aesthetic balance and ease of writing. In the case of doku, the strokes that make up the left half are collectively called the kemono-hen, or “beast radical,” which is an altered form of the kanji…

…which means “dog.” The right half of doku, by the way, is written exactly like the kanji for mushi, or “bug,” but is actually held to be a modified form of…

…which is related to the concept of avarice, leading to the image of a covetous animal taking things for itself and not showing interested in being part of a group, thus the meaning of “alone” associated with doku.

Schmitz contends that the presence of the animal-based kemono-hen within the kanji used for Germany carries discriminatory connotations. While he hasn’t filed any official complaints with the Japanese government or educational authorities, he has said that “As a German who understands kanji, I would like to see a change.”

However, Schmitz is not asking for Japanese society to decide on new kanji to use for Germany, nor for the doku kanji to be recast without use of the kemono-hen. Instead, he’s voiced his hope that instead of using kanji at all to refer to Germany, media outlets will begin rendering the country’s name using the phonetic, intrinsically meaningless katakana script in all instances, thus removing any unwanted association with the base origins of the kanji and utilizing the purpose for which katakana were developed.

Source: Tokyo Shimbun via Hachima Kiko, OK Jiten, Goi Jiten, Kanji Chishiki

Top image: Wikipedia/Anomie (edited by RocketNews24)

Insert images: RocketNew24

Follow Casey on Twitter, where he’s pretty much OK with America being “Rice Country” in its official kanji.

Twitter users say Japanese Prime Minister’s name is hiding in the kanji for Japan’s new era name

Twitter users say Japanese Prime Minister’s name is hiding in the kanji for Japan’s new era name Foreigners misreading Japanese kanji of “two men one woman” is too pure for Japanese Internet

Foreigners misreading Japanese kanji of “two men one woman” is too pure for Japanese Internet Four new era names the Japanese government rejected before deciding on Reiwa

Four new era names the Japanese government rejected before deciding on Reiwa Japanese study tip: Imagine kanji characters as fighting game characters, like in this cool video

Japanese study tip: Imagine kanji characters as fighting game characters, like in this cool video Pokémon Center apologizes for writing model Nicole Fujita’s name as Nicole Fujita

Pokémon Center apologizes for writing model Nicole Fujita’s name as Nicole Fujita Red light district sushi restaurant in Tokyo shows us just how wrong we were about it

Red light district sushi restaurant in Tokyo shows us just how wrong we were about it Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes

Japanese ramen restaurants under pressure from new yen banknotes McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods

McDonald’s new Happy Meals offer up cute and practical Sanrio lifestyle goods Akihabara pop-up shop sells goods made by Japanese prison inmates

Akihabara pop-up shop sells goods made by Japanese prison inmates Tokyo Tsukiji fish market site to be redeveloped with 50,000-seat stadium, hotel, shopping center

Tokyo Tsukiji fish market site to be redeveloped with 50,000-seat stadium, hotel, shopping center Sandwiches fit for a sumo served up in Osaka【Taste Test】

Sandwiches fit for a sumo served up in Osaka【Taste Test】 Starbucks Japan adds a Motto Frappuccino to the menu for a limited time

Starbucks Japan adds a Motto Frappuccino to the menu for a limited time French Fries Bread in Tokyo’s Shibuya becomes a hit on social media

French Fries Bread in Tokyo’s Shibuya becomes a hit on social media We tried Korea’s way-too-big King Tonkatsu Burger at Lotteria 【Taste Test】

We tried Korea’s way-too-big King Tonkatsu Burger at Lotteria 【Taste Test】 Beautiful Ghibli sealing wax kits let you create accessories and elegant letter decorations【Pics】

Beautiful Ghibli sealing wax kits let you create accessories and elegant letter decorations【Pics】 All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge

All-you-can-drink Starbucks and amazing views part of Tokyo’s new 170 meter-high sky lounge More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month

More foreign tourists than ever before in history visited Japan last month Studio Ghibli releases new action figures featuring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind characters

Studio Ghibli releases new action figures featuring Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind characters New private rooms on Tokaido Shinkansen change the way we travel from Tokyo to Kyoto

New private rooms on Tokaido Shinkansen change the way we travel from Tokyo to Kyoto Starbucks reopens at Shibuya Scramble Crossing with new look and design concept

Starbucks reopens at Shibuya Scramble Crossing with new look and design concept Studio Ghibli glasses cases let anime characters keep an eye on your spectacles

Studio Ghibli glasses cases let anime characters keep an eye on your spectacles Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan

Studio Ghibli releases Kiki’s Delivery Service chocolate cake pouches in Japan New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers

New definition of “Japanese whiskey” goes into effect to prevent fakes from fooling overseas buyers Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things

Our Japanese reporter visits Costco in the U.S., finds super American and very Japanese things Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro

Studio Ghibli unveils Mother’s Day gift set that captures the love in My Neighbour Totoro New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty

New Japanese KitKat flavour stars Sanrio characters, including Hello Kitty New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions

New Pokémon cakes let you eat your way through Pikachu and all the Eevee evolutions Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo

Disney princesses get official manga makeovers for Manga Princess Cafe opening in Tokyo Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely

Sales of Japan’s most convenient train ticket/shopping payment cards suspended indefinitely Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season

Sold-out Studio Ghibli desktop humidifiers are back so Totoro can help you through the dry season Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s

Japanese government to make first change to romanization spelling rules since the 1950s Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design

Ghibli founders Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki contribute to Japanese whisky Totoro label design Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】

Doraemon found buried at sea as scene from 1993 anime becomes real life【Photos】 Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed

Tokyo’s most famous Starbucks is closed One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions

One Piece characters’ nationalities revealed, but fans have mixed opinions We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint

We asked a Uniqlo employee what four things we should buy and their suggestions didn’t disappoint Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan

Princesses, fruits, and blacksmiths: Study reveals the 30 most unusual family names in Japan W.T.F. Japan: Top 5 most difficult kanji ever【Weird Top Five】

W.T.F. Japan: Top 5 most difficult kanji ever【Weird Top Five】 The hidden meaning of the U.S. Air Force’s “shake and fries” patch in Japan

The hidden meaning of the U.S. Air Force’s “shake and fries” patch in Japan Foreigners in Japan vote for the best-looking katakana character

Foreigners in Japan vote for the best-looking katakana character Renowned Japanese calligraphy teacher ranks the top 10 kanji that foreigners like

Renowned Japanese calligraphy teacher ranks the top 10 kanji that foreigners like Japan announces Kanji of the Year for 2019, and it was really the only logical choice

Japan announces Kanji of the Year for 2019, and it was really the only logical choice Tired of wasting paper practicing your kanji? Try these reusable water-activated practice sheets

Tired of wasting paper practicing your kanji? Try these reusable water-activated practice sheets What’s funnier and more likely to make you study than poo? How about male pattern baldness?

What’s funnier and more likely to make you study than poo? How about male pattern baldness? How do deep-fried frog burgers taste? We find out at Yokohama cafe 【Taste test】

How do deep-fried frog burgers taste? We find out at Yokohama cafe 【Taste test】 Japan’s kanji character of the year for 2017 is “north”

Japan’s kanji character of the year for 2017 is “north” “Disaster”: 2018 Kanji of the Year unveiled by Buddhist monk at Kiyomizudera temple in Kyoto

“Disaster”: 2018 Kanji of the Year unveiled by Buddhist monk at Kiyomizudera temple in Kyoto Kanji fail — Japanese parents shocked to learn their baby girl’s name has inappropriate meaning

Kanji fail — Japanese parents shocked to learn their baby girl’s name has inappropriate meaning “Gold” named 2016 Kanji of the Year

“Gold” named 2016 Kanji of the Year Japanese writing system gets turned into handsome anime men with Hiragana Boys video game

Japanese writing system gets turned into handsome anime men with Hiragana Boys video game Kanji Tetris is the coolest way to practice and play with Japanese that we’ve ever seen【Video】

Kanji Tetris is the coolest way to practice and play with Japanese that we’ve ever seen【Video】 Poop Kanji-Drill toilet paper is the best way to accomplish your Japanese studying doo-ties

Poop Kanji-Drill toilet paper is the best way to accomplish your Japanese studying doo-ties

Leave a Reply